Approval voting

Template:Mergefrom Majority Choice Approval Approval voting is a voting system used for elections, in which each voter can vote for as many or as few candidates as the voter chooses. It is typically used for single-winner elections but can be extended to multiple winners. Approval voting is a limited form of range voting, where the range that voters are allowed to express is extremely constrained: accept or not.

Procedures

Each voter may vote for as many options as they wish, at most once per option. This is equivalent to saying that each voter may "approve" or "disapprove" each option by voting or not voting for it, and it's also equivalent to voting +1 or 0 in a range voting system.

The votes for each option are tallied. The option with the most votes wins.

Example

Imagine that Tennessee is having an election on the location of its capital. The population of Tennessee is concentrated around its four major cities, which are spread throughout the state. For this example, suppose that the entire electorate lives in these four cities, and that everyone wants to live as near the capital as possible.

The candidates for the capital are:

- Memphis, the state's largest city, with 42% of the voters, but located far from the other cities

- Nashville, with 26% of the voters, near the center of Tennessee

- Knoxville, with 17% of the voters

- Chattanooga, with 15% of the voters

The preferences of the voters would be divided like this:

| 42% of voters (close to Memphis) |

26% of voters (close to Nashville) |

15% of voters (close to Chattanooga) |

17% of voters (close to Knoxville) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Supposing that voters voted for their two favorite candidates, the results would be as follows (a more sophisticated approach to voting is discussed below):

- Memphis: 42 total votes

- Nashville: 68 total votes

- Chattanooga: 58 total votes

- Knoxville: 32 total votes

Potential for tactical voting

Approval voting passes a form of the monotonicity criterion, in that voting for a candidate never lowers that candidate's chance of winning. Indeed, there is never a reason for a voter to tactically vote for a candidate X without voting for all candidates he or she prefers to candidate X.

However, as approval voting does not offer a single method of expressing sincere preferences, but rather a plethora of them, voters are encouraged to analyze their fellow voters' preferences and use that information to decide which candidates to vote for.

A good tactic is to vote for every candidate the voter prefers to the leading candidate, and to also vote for the leading candidate if that candidate is preferred to the current second-place candidate. When all voters use this tactic, the Condorcet winner is almost certain to win.

In the above election, if Chattanooga is perceived as the strongest challenger to Nashville, voters from Nashville will only vote for Nashville, because it is the leading candidate and they prefer no alternative to it. Voters from Chattanooga and Knoxville will withdraw their support from Nashville, the leading candidate, because they do not support it over Chattanooga. The new results would be:

- Memphis: 42

- Nashville: 68

- Chattanooga: 32

- Knoxville: 32

If, however, Memphis were perceived as the strongest challenger, voters from Memphis would withdraw their votes from Nashville, whereas voters from Chattanooga and Knoxville would support Nashville over Memphis. The results would then be:

- Memphis: 42

- Nashville: 58

- Chattanooga: 32

- Knoxville: 32

Effect on elections

The effect of this system as an electoral reform is disputed. Instant-runoff voting advocates like the Center for Voting and Democracy argue that Approval Voting would lead to the election of "compromise candidates" disliked by few, and liked by few. A study by Approval advocates Steven Brams and Dudley R. Herschbach published in Science in 2000 argued that approval voting was "fairer" than preference voting on a number of criteria. They claimed that a close analysis shows that the hesitation to support a 'compromise candidate' to the same degree as one supports one's first choice (as approval voting requires) actually outweighs the extra votes that such second choices get. Accordingly, preference voting is more biased towards compromise candidates than approval voting - a non-obvious and surprising result. The United States organiation Citizens for Approval Voting was organized in December 2002 to promote the use of approval voting in all public single-winner elections.

Other issues and comparisons

Advocates of approval voting often note that a single simple ballot can serve for single, multiple, or negative choices. It requires the voter to think carefully about who or what they really accept, rather than trusting a system of tallying or compromising by formal ranking or counting. Compromises happen but they are explicit, and chosen by the voter, not by the ballot counting. Some features of approval voting include:

- Unlike Condorcet method, instant-runoff voting, and other methods that require ranking candidates, approval voting does not require significant changes in ballot design, voting procedures or equipment, and it is easier for voters to use and understand. This reduces problems with mismarked ballots, disputed results and recounts.

- Increasing options for voters, when compared with the common first-past-the-post system, could increase voter turnout

- It provides less incentive for negative campaigning than many other systems.

- It allows voters to express tolerances but not preferences. Some political scientists consider this a major advantage, especially where acceptable choices are more important than popular choices.

- Each voter may vote as many times as they wish, at most once per candidate. This is equivalent to saying that each voter may "approve" or "disapprove" each candidate by voting or not voting for them, and it's also equivalent to voting +1 or 0 in a range voting system.

- It is easily reversed as disapproval voting where a choice is disavowed, as is already required in other measures in politics (e.g. representative recall).

Multiple winners

Approval voting can be extended to multiple winner elections, either as block approval voting, a simple variant on block voting where each voter can select an unlimited number of candidates and the candidates with the most approval votes win, or as proportional approval voting which seeks to maximise the overall satisfaction with the final result using approval voting.

Relation to effectiveness of choices

Operations research has shown that the effectiveness of a policy and thereby a leader who sets several policies will be sigmoidally related to the level of approval associated with that policy or leader. There is an acceptance level below which effectiveness is very low and above which it is very high. More than one candidate may be in the effective region, or all candidates may be in the ineffective region. Approval voting attempts to ensure that the most-approved candidate is selected, maximizing the chance that the resulting policies will be effective.

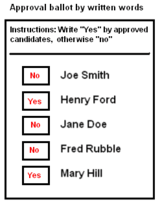

Ballot types

Approval ballots can be of at least four semi-distinct forms. The simplest form is a blank ballot where the names of supported candidates is written in by hand. A more structured ballot will list all the candidates and allow a mark or word to be made by each supported candidate. A more explicit structured ballot can list the candidates and give two choices by each. (Candidate list ballots can include spaces for write-in candidates as well.)

|

|

|

|

All four ballots are interchangeable. The more structured ballots may aid voters in offering clear votes so they explicitly know all their choices. The Yes/No format can help to detect an "undervote" when a candidate is left unmarked, and allow the voter a second chance to confirm the ballot markings are correct.

See also

- List of democracy and elections-related topics

- Borda count

- Bucklin voting

- First Past the Post electoral system (also called Plurality or Relative Majority)

- Condorcet method

- Cloneproof Schwartz Sequential Dropping

- Instant-runoff voting

- Voting system - many other ways of voting

External links

- Approval Voting Home Page

- Citizens for Approval Voting

- Americans for Approval Voting

- electionmethods.org on approval voting

- "The Science of Elections", Steven J. Brams and Dudley R. Herschbach, Science May 25, 2001: 1449.

- Rebuttal to "The Science of Elections", Center for Voting and Democracy.